PSYCHOLOGY OF US

YOUR RESOURCE LIBRARY

The Science Behind Stress

Stress is the way that our mind and body react to demands or threats. Whereas anxiety is worry about what might happen in the future, stress is the response to what is happening now.

Why We Experience Stress

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has been studying emotions for over 30 years. Damasio suggests that all emotions, positive and negative, have evolutionary functions geared towards our survival (1).

Emotions are motivators that have evolved over millions of years.

Each emotion is made up of neurochemicals that motivate us to fulfill certain basic needs: rest, bonding, resources, and safety (2).

How stress protects us.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the amygdala. It is the lightning-fast brain section responsible for detecting potential threats and prompting fear responses, such as fight-or-flight. The amygdala sends signals to the hypothalamus to release bursts of stress hormones, which promote arousal and prompt us to enact safety strategies.

Fear responses are not only activated by life or death situations. A stress response (a milder fear response) can be activated whenever we feel vulnerable, protecting us against possible negative feelings as well as physical harm. Even a remote threat of shame, failure, or loss can trigger a stress response.

How stress hinders us.

Fear responses are very effective at keeping us safe but there is a downside. Sometimes when the amygdala senses danger, it actually blocks our critical thinking in order to react swiftly. This may save our life but it may also mean that we overreact or have an emotional outburst that leaves us feeling perplexed, ashamed, or remorseful later. Emotional Intelligence author Daniel Goleman calls this experience an Amygdala Hijack (3).

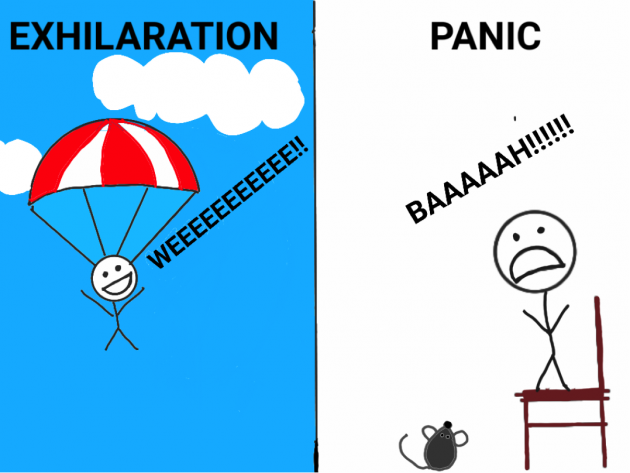

Distress or Eustress?

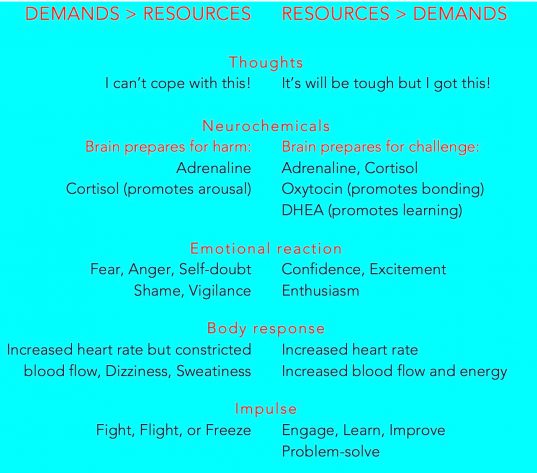

The way that our brains react to stress depends, in part, on how well we think that we can cope with it. The Upside of Stress author, Kelly McGonigal, points out that when we perceive a stressor to be overwhelming, our brains react with fight-or-flight responses. However, if we view a stressor as manageable, we have other stress responses that help us step up to the challenge (4). These types of stress responses are often distress (or negative stress) and eustress (positive stress). Here are some examples:

- Fight. Fight doesn’t necessarily mean that we lash out; rather we may become defensive or show resistance in other ways.

- Flight. If we think that we can’t change our situation, that resistance will not protect us, or if the resulting conflict seems too threatening, we may withdraw to avoid stressors.

- Brain freeze. We may shut down to cope with stressors. We may feel stuck, unable to move forward, so we don’t. do. anything. We stagnate instead, in hopes that the issue will resolve itself.

- Fawn. Submission, subservience, or people pleasing.

- Tend & Befriend. Similar to Fawn, our brain drives us to bond with others for strength. Connecting with our friends, family, or community releases neurochemicals called endorphins and oxytocin, which enable us to experience pain relief and bonding.

- Challenge. Our bodies prepare us for the challenge by increasing energy and blood flow, strengthening confidence, and enhancing our focus and memory.

Our brain still releases bursts of stress hormones (adrenaline and cortisol) but it also releases oxytocin (promoting bonding) and DHEA, a brain chemical that helps our brains grow from stressful experiences, counters the stressful effects of cortisol, and enhances healing.

- Excite-Delight. Intense stress can even be exciting! When we perceive dangerous circumstances as recreational, our brain releases a chemical cocktail (endorphins, adrenaline, testosterone, dopamine) that makes extreme sports enjoyable. This also applies to watching scary movies and falling in love.

A response may fall into the category of distress in one scenario and eustress in another. For example, a Fight response may enable us escape danger or embarrass us if it seems out of proportion. We may easily switch between distress and eustress responses. An activity like skiing can trigger an Excite-Delight response that intensifies to a Freeze response when it becomes tiring and overwhelming (5).

What determines which stress response is triggered in our brain?

Whether we find a situation distressing or eustress-ing has less to do with whether the stressor is threatening and more to do with whether we think we can handle it (4). If we perceive a challenge to outweigh our coping resources, then our amygdala will react with a fight-or-flight response. If we think that we have the resources to cope, our brain enacts healthier stress responses such as the Challenge or Excite-Delight responses listed above.

The good news is that we can train our minds and bodies to cope better with stress, making it more likely that our brains react to stressors with eustress instead of distress. However, sometimes life circumstances are so distressing that we can´t help but feel overwhelmed. Some examples are bullying or abusive relationships, crisis situations, or past tragedies and losses that still haunt us.

If you feel overwhelmed to the point that your ability to function in everyday life is impaired, the other posts on this site address the more severe effects of ongoing stress: Anxiety, Trauma, Depression. You don’t have to go through this alone. You can contact me for Skype sessions. Or seek the help of a professional in your area. Seeking help can change your life.

Find out more: How Monkey Therapy Helps You Get Better at Stress.

References and Contributors

Anthony Damasio. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (2005).

Paul Gilbert. The Compassionate Mind. Compassion Focused Therapy (2010).

Daniel Goleman. Emotional Intelligence. (1996).

Kelly McGonigal. The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It (2015).

Donald Meichenbaum. Stress Inoculation Training (1985).

Daniel Collerton. (2016). Psychotherapy and brain plasticity. Frontiers in Psychology.

Rick Hanson. (2013). Hardwiring Happiness. The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm and Confidence.

Hasse Karlsson. (2011). How Psychotherapy Changes the Brain. Psychiatric Times.

Joseph LeDoux. (1996). The Emotional Brain.

Joseph LeDoux. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron.

Joseph LeDoux. (2015). Feelings: What are they and how does the brain make them? Daedalus.

Karla McLaren. (2013). The Art of Empathy: A Complete Guide to Life’s Most Essential Skill.

Catherine Pittman & Elizabeth Karle. (2015). Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry.

Dan Siegel. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation.

Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

How therapy works

Worksheets and useful information

Creative Process

Feeling Stuck

Stress

Depression

Feeling Down

Anxiety

Guilt and shame

Find out more

What I do differently

Monkey Therapy

Transformational Coaching

Online Therapy

Trauma

Your inner critic

The science behind it

Steps you can take now

Publications

More than CBT

More than IFS

Psychedelics

Neurodiversity

Thank you!

Your message has been sent. We'll contact you shortly

© 2023 The Monkey Therapist. All Rights Reserved. Site Designed By Samantha Ósk

PRIVACY POLICY