PSYCHOLOGY OF US

YOUR RESOURCE LIBRARY

SHAME

The world’s most sensible person and the biggest idiot both stay within us. The worst part is, you can’t even tell who is who. -Chetan Bhagat

Contents:

What is shame?

Shame is Useful

Shame Harms Us

Overactive Shame

Symptoms of Overactive Shame

What is shame?

Whereas guilt arises when we think that we have done something bad, shame occurs when we believe that we are bad (and perhaps that is the reason that we have done something bad).

Though different, guilt and shame are intertwined. Guilt could be considered shame’s more functional cousin. To understand shame, we need to look at guilt too. The following points out how shame and guilt can be useful, explains the damaging impact of shaming, and how psychotherapy can help you alleviate your shame.

Guilt is Useful

The punitive feelings of guilt act as boundaries that contain our behaviour. Our internal guide helps us to maintain friendships, empathise with others and be accepted in our chosen communities. Guilt motivates us to avoid harming others and to rectify or apologise if we do. Guilt promotes learning and learning mitigates regret. Learning a lesson can make meaning of past mistakes even when the harm or loss has already occurred.

Shame is Useful

If you’ve read much of the negative press out there on shame, you might wonder, can shame actually be useful? The short answer to this question is Yes …and No. Shame may be useful, but it is not always constructive. We use shame as a tool to control ourselves and to control others, but often it’s at a cost.

Shame on me

Similarly to guilt, shame prevents us from damaging our relationships and motivates us to repair them. It serves as an internal policing function, inhibiting us from acting on desires that threaten our personal identities (for example, I’m a good person; I could never do ……). Or shame can motivate us to change.

Consider an instance in which someone drives home drunk. Even if nothing bad happened at the time, the belief that, If I drive drunk, then I am reckless, can trigger shame and motivate them to change their behaviour.

Shame may motivate us to strive harder. It involves aspects of comparison to others, social ideas, and values; but also comparison of who we are and who we wish to be. Shame can function as a teacher, solidifying our personal boundaries or standards.

Often perfectionists are motivated by shame. Perfectionists drive themselves to achieve by striving to not fail. Striving harder often pays off with better results. On the downside, the internal shaming voice becomes stronger.

Shame on You

Deliberate finger-pointing is often used to inhibit another person’s self-expression and desires that conflict with the norms of society or a particular group. An example of this is slut-shaming or labelling a female’s perceived behaviour as morally corrupt. Slut-shaming is a form of sexism that aims to disempower the receiver.

Shaming can also create and strengthen group identity. An effective way to create an in-group is to define the out-group. This is an age-old political tactic. Political campaigns label a particular minority as dangerous in an attempt to incite fear of the out-group and to create a self-protective coalition against it.

Shaming others or scapegoating is used to distract from any wrongdoing on the part of the shamer. For example, one might blame her anger outbursts on her partner (who ‘always provokes her’) rather than on her short temper.

Shame is often used as a tool to exert control in a relationship. For example, You are always late. You are so selfish. One might threaten to leave his partner if certain behaviours do not change. This type of shaming attempts to motivate the partner to repair issues within the relationship.

Shame Harms Us

Though the intentions and functions of shame and guilt are similar – shame could be considered guilt’s more sinister cousin. Shaming may be very effective in changing one’s behaviour in the short-term but shaming tends to have a corrosive effect on the receiver, on relationships, and even on the shamer.

Shame on me

When we feel ashamed, we often believe that we are not able to control what happens in our lives. For example, we may believe that we are inherently useless. Shaming hijacks our sense of agency; our self-critical voice depletes our mental energy and its internal focus distracts us from finding external solutions.

Because we cannot change the shameful part of ourselves, we want to hide, avoid, ignore or escape. We attack ourselves or we attack others by blaming or scapegoating. As a result, shame can cause stress, demotivation, or extreme distress and impairment.

Shame on you

Intense shaming is a form of bullying or emotional abuse. It often has a toxic impact on the receiver, who feels inferior, disempowered and trapped. If the receiver is unable to leave the relationship or change the relational pattern, shaming can lead to distress, depression, or anxiety.

The shamer may also suffer from the effects of their shaming behaviour. People close to them may show resentment, hide their behaviours, lie to avoid criticism, shame in return, or they may end the relationship to stop the shaming.

Often, when we shame others, it is because we feel ashamed ourselves. Shamers may also be subjected to their own punishing criticism.

Overactive Shame

We all feel ashamed at times but if feelings of shame are ongoing, excessive, or overwhelming, it may be a sign of overactive shame.

Causes (or origins) of Overactive Shame

Many times, excessive shame originates in childhood and continues into adulthood. An enduring sense of shame can stem from having had emotionally unavailable or physically absent parents or being a part of a shame-based culture or religion. Children who have been abused, bullied, or victimized often feel shame about their role in the abuse or inability to stop it. Overactive shame may develop as a result, especially when adults blame children or do not take steps to assure them that they were blameless.

Life struggles such as divorce, infidelity, loss, financial or work difficulties, acts of violence, or injurious accidents can lead to excessive shame, either self-induced or through the blame of others.

How Overactive Shame Works

Shame hides. It’s as if it is ashamed of itself. Often we have lived with shame for so long, we are unaware that it is there, driving our beliefs, actions, and emotions.

Shame maintains itself. When we feel ashamed, we are less likely to try to repair the damage, reconnect with the hurt party, or learn from the experience. And when we fail to make amends, the negative experience is added to the evidence that supports the underlying belief that we are defective in the first place. A shame cycle begins, in which we repeat destructive behaviours because we don’t believe that we have the ability to change.

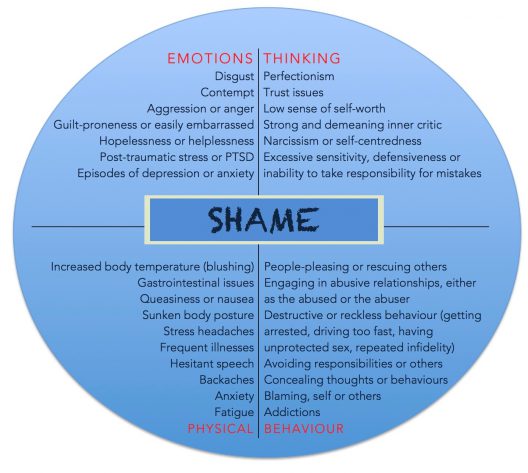

Symptoms of Overactive Shame

The very nature of shame means that it is often outside of our awareness so identifying symptoms can be difficult. As seen above, the underlying negative beliefs causing our shame – I am not good enough, I am not smart enough, I am unlovable – are deep-rooted and make us vulnerable. So shame is buried under other emotions (depression, anger, guilt) and behaviour (defensiveness). Below are common symptoms:

FIND OUT MORE: How Monkey Therapy Helps You Beat Overactive Shame. The Science Behind Guilt and Shame. Steps You Can Take Now to Defuse Your Inner Critic.

Referenced and Contributors

-

Paul Gilbert. (2010). The Compassionate Mind.

-

Joseph LeDoux. (2015). Feelings: What are they and how does the brain make them? Daedalus.

-

Wendy Dryden. (2014). Shame and the Motivation to Change the Self. Emotion.

-

Gershen Kaufman. (1993). Shame: The Power of Caring.

-

Todd Kashdan. (2015). The Power of Negative Emotion: How Anger, Guilt, and

Self Doubt are Essential to Success and Fulfillment.

-

Kelly McGonigal. (2015). The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It.

-

Karla McLaren. (2010). The Language of Emotions: What Your Feelings Are Trying to Tell You.

-

Daniel Sznycer, John Tooby, Leda Cosmides, Roni Porat, Shaul Shalvi, & Eran Halperin. (2016). Shame closely tracks the threat of devaluation by others, even across cultures. Social Sciences. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences.

-

Sandra Wilson. (2010). Hurt People Hurt People: Hope and Healing for Yourself and Your Relationships.

How therapy works

Worksheets and useful information

Creative Process

Feeling Stuck

Stress

Depression

Feeling Down

Anxiety

Guilt and shame

Find out more

What I do differently

Monkey Therapy

Transformational Coaching

Online Therapy

Trauma

Your inner critic

The science behind it

Steps you can take now

Publications

More than CBT

More than IFS

Psychedelics

Neurodiversity

Thank you!

Your message has been sent. We'll contact you shortly

© 2023 The Monkey Therapist. All Rights Reserved. Site Designed By Samantha Ósk

PRIVACY POLICY