PSYCHOLOGY OF US

YOUR RESOURCE LIBRARY

TRAUMATIC MEMORIES

If you hide your trauma from yourself, you are likely to react like an animal in a thunderstorm, having a full body response to the hormones that signal danger. Without language or context, your awareness may be limited to ‘I am scared’. Yet, determined to stay in control, you are likely to avoid anybody or anything that reminds you even vaguely of your trauma. You may also alternate between being inhibited or being uptight, reactive, or explosive. All without knowing why. –Bessel van der Kolk

Contents:

How Memory Works

Causes of Traumatic Memories

Case Example: How an event becomes a traumatic memory

Post-traumatic Stress Signs and PTSD Symptoms

What Makes a Difference in How We Process Trauma

How Memory Works

Everyday Memories

Long-term memory is the brain’s encoding of our experiences. It is made up of our past experiences (or rather the stories that we tell ourselves about our experiences). Like stories, they have a linear quality, a beginning, middle and an end. But our memories are made up of far more than our recollections. Our memories are made up of images and emotions as well. Though we often think that our brains work like computers, in that we store one movie in one file, our memories are actually stored in two places: emotional part of our brains and the sense-making part of our brains.

Ever wondered how we can feel emotional in a situation and not know why?

Ever walk into a room and instantly feel uneasy? This perplexing event can be attributed to memory storage. When we have an experience, our senses of it (images, sounds, smells), the way we feel about it, and the physical sensations we experience are all stored in the emotional part of our brains and the accompanying language and context is encoded in the sense-making part of our brains.

With everyday memories, these two memory systems communicate and we easily make sense of our sensory and emotional experiences with language. For instance, the smell of gingerbread triggers an emotional memory and we feel happy as a result. Our thinking brain then provides context, reminding us that we loved eating gingerbread during the holidays at grandma’s house.

We have tens of thousands of experiences during our lifetimes and we are incapable of remembering all of them. But the sensory and emotional imprint of our experiences remain long after we have lost conscious recollection of what formed them. Emotional memories shape our perceptions, expectations, and reactions, sometimes without us even realising it. This is why we can feel emotions (such as uneasiness or even fear) in a situation without knowing why.

Traumatic Memories

When we feel overwhelmed, our brains react with stress hormones – adrenaline and cortisol – which energise us to protect ourselves. These brain chemicals actually block the thinking part of our brain in order to enable us to react quickly. The downside is that our emotional memories (images, smells, physical sensations) don’t always integrate with our thinking brain memory (facts, language, events) as a result. So we become emotionally conditioned to feel fear whenever we experience something that reminds us of the trauma even though we are consciously aware that we are no longer in danger.

Developing hyper-alertness. After a traumatic event, our brains may become hyper-sensitized to anything that resembles the frightening experience. Our bodies react as if the trauma is happening again, even if when are not consciously aware of it. So, we often feel scared or anxious in normal situations and don’t know why.

Caught in a trauma loop. If traumatic memories are not addressed, we may become stuck on hyper-alert. We may develop a tendency to interpret our anxious feelings and body sensations as evidence that there is potential danger. Because anxiety is highly unpleasant, we may avoid similar situations and miss opportunities to overcome our fears. The more that we avoid anxiety-provoking situations, the more entrenched our fears become. Consequently, a trauma loop occurs and becomes increasingly difficult to break.

Causes of Traumatic Memories

Trauma is any experience that overwhelms our normal capacities to cope. The diagnostic manual of psychological disorders (DSM-V) lists major traumatic events that often (but not always) lead to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD):

– Exposure to death (e.g. traffic accidents or combat)

– Threat of death (violence at home or on the street)

– Serious injury (e.g. natural disasters)

– Sexual abuse

However, Trauma expert, Bessel van der Kolk, adds that it is not only extreme experiences that can be overwhelming. Some experiences may be traumatic for some people but not for everyone.

– Losing a home to a mortgage foreclosure

– Feeling humiliated in front of strangers

– Being in a car accident, or witnessing a car accident

– Neglect or abuse

– Miscarriage

– Family disturbance

– End of a long-term relationship or divorce

– Job loss or redundancy

– The death of a loved one (1)

Most people have had a negative experience that overwhelmed their ability to cope at the time. But the way that we process traumatic experiences varies from person to person. And influential factors (such as whether the trauma was a singular or on going occurrence) contribute to our ability to process the trauma. Below is an example to demonstrate.

How a Traumatic Memory Develops and Manifests Over Time

Danger Mouse

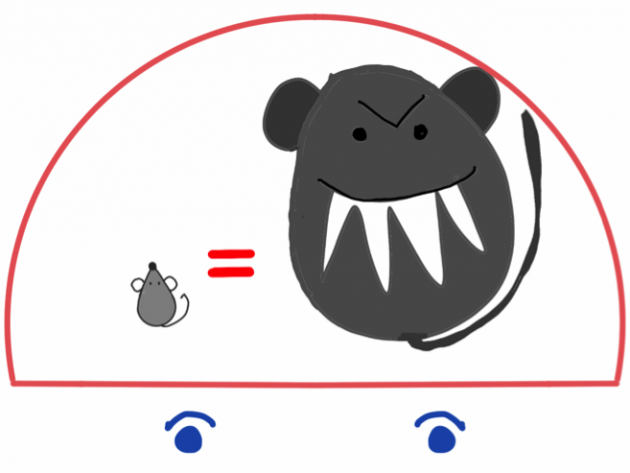

As a toddler, Tomas was often left on his own while his mother, a single parent, went shopping. On one occasion a rat scurried into the room looking for food, brazenly brushing against him. Tomas screamed for his mother, but she didn’t appear. By the time she walked into the room, little Tomas was exhausted from fever-pitch screaming. This is what was happening in Tomas’ mind, brain, and body:

Tomas saw the rat near him and he felt fear. His brain released cortisol and adrenaline, preparing him to flee; but he was unable to escape the room. Feeling helpless and alone, Tomas began to panic. More stress hormones were released and Tomas screamed louder. When his mother did not return, his brain flooded with cortisol and any thinking brain attempts to quell his fear response were blocked.

The frightening experience is encoded into Tomas’s emotional memory. Emotional brain associates rats with danger. Also being left alone is linked with terror and sadness. Tomas screams uncontrollably any time his mother leaves him alone.

When Tomas moves away to college, he encounters a mouse in his apartment, which instantly triggers his fear and releases a large rush of cortisol and adrenaline. Before he is even aware of it, Tomas has shouted and jumped up on a chair. Tomas is surprised and slightly embarrassed by his own response but he doesn’t get off the chair until the mouse is gone.

Since he moved into his own apartment, Tomas also has trouble sleeping. Though he doesn’t know why, Tomas hates being alone. Because he often feels anxious for no reason, he avoids being alone. He worries about being able to cope with his negative emotions, which triggers further anxiety.

Trauma Loop: Tomas becomes hypersensitive. New stimuli begin to trigger Tomas’s fear. Tomas´s general anxiety heightens. Walking alone, he jumps when he sees any dogs, even friendly ones. The anxiety that he feels when he is alone develops into an anticipatory fear; he develops a fear of the anxious feelings that he might feel when he is alone again.

Trauma loop: safety strategies. Avoidance: Tomas goes out most nights to avoid being at home alone. Numbing: He drinks to numb the anxiety of returning home to help him sleep. He wakes up in the early morning hours when the alcohol wears off. His anxious feelings keep him awake reinforcing the being alone anxiety loop.

What Makes a Difference in How We Process Trauma

In the above example, the rat event was a traumatic trigger for Tomas but other factors contributed to how his brain processed this memory.

Research shows that we are more likely to remember a traumatic event if it is a singular event, with a natural or accidental cause, for which we later receive validation or support. Feeling safe enough to re-tell the story again and again also lessens its impact.

On the other hand, we are more likely to lose explicit memory of the traumatic event if the event is recurring, deliberate, and/or there is denial or secrecy involved. Such factors make sense when we consider that our brains integrate memories by making sense of them. It is easier for us to make sense of a natural disaster than it is to make sense of abuse or neglect from a trusted relative.

For example, Tomas’s trauma may have manifested differently if being left alone was a singular incident. In an alternative cartoon strip, Tomas’s mother might have been unexpectedly called away to help a neighbour. She rushes home, chases the rat away and soothes her distressed son. When she retells this story she does so with empathy for Tomas. If this were the case, the trauma may have integrated with Tomas’ explicit (thinking brain) memory and his understanding of the trauma might change how he reacted to future triggers. Being alone would not have the same significance and he might startle and laugh whenever he saw a mouse instead of feeling distressed, helpless, and perplexed.

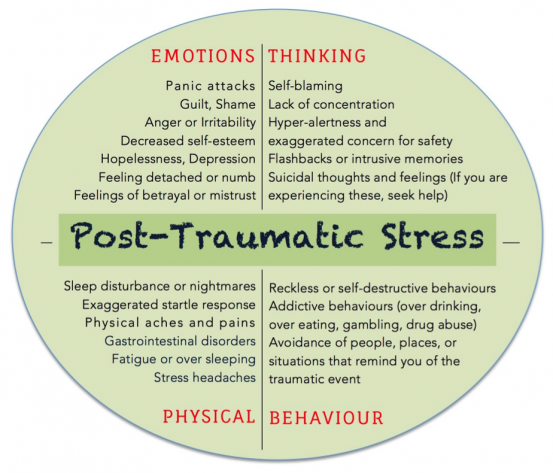

Post-traumatic Stress Signs and PTSD Symptoms

These symptoms most often occur hours or days following a traumatic event. However, it sometimes takes weeks, months, or even years before they occur. This may make it hard to recognise symptoms as being connected to past trauma.

These are common reactions to traumatic experiences and are likely to occur following a traumatic event. However, if they persist for more than a few weeks, you may be experiencing post-traumatic stress or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD diagnosis depends on how many reactions you are experiencing, and how frequent, severe and disabling they are to you.

Helpguide.org, Overcoming Traumatic Stress, Ann Wetmore and Claudia Herbert

The good news is that post-traumatic stress is treatable.

New (amazing) studies using live brain scans (fMRIs) show that our brain has a surprising amount of neuroplasticity which means that we can reshape and retrain our brain to respond differently to stimuli no matter how old we are.

FIND OUT MORE: Trauma Recovery with Monkey therapy. The Science of Tramatic Memories. Steps You Can Take Now to Address Trauma.

References

- Alan Baddely. (2016). Memory and Learning. The Brain From Top to Bottom. http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_07/a_07_p/a_07_p_tra/a_07_p_tra.html

- Ruth Buczynski & Peter Levine. (2016). Why It’s Critical to Understand the Role of Memory In Trauma Therapy.

- Anthony Damasio. (2005). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain.

- Paul Gilbert. (2010). The Compassionate Mind.

- Helpguide.org. (2016). Traumatic Stress. Recovering from the Stress of Experiencing or Being Exposed to Traumatic Events. http://www.helpguide.org/articles/ptsd-trauma/traumatic-stress.htm

- Joseph Ledoux. (1998). The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life.

- Joseph Ledoux. (2007). Emotional Memory. Scholarpedia.

- DE Linden. (2006). How Psychotherapy Changes the Brain: The Contribution of Functional Neuroimaging. Molecular Psychiatry.

- Catherine Pittman & Elizabeth Karle. (2015). Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry.

- Dan Siegel. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation.

- Dan Siegel. (2010). The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration

- Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

- Ann Wetmore & Claudia Herbert. (2008). Overcoming Traumatic Stress: A Self-Help Guide Using Cognitive Behavioral Techniques: A Self-help Guide Using Cognitive Behavioural Techniques.

How therapy works

Worksheets and useful information

Creative Process

Feeling Stuck

Stress

Depression

Feeling Down

Anxiety

Guilt and shame

Find out more

What I do differently

Monkey Therapy

Transformational Coaching

Online Therapy

Trauma

Your inner critic

The science behind it

Steps you can take now

Publications

More than CBT

More than IFS

Psychedelics

Neurodiversity

Thank you!

Your message has been sent. We'll contact you shortly

© 2023 The Monkey Therapist. All Rights Reserved. Site Designed By Samantha Ósk

PRIVACY POLICY