PSYCHOLOGY OF US

YOUR RESOURCE LIBRARY

Steps You Can Take Now to Defuse Your Inner Critics

Our inner critics can be erosive, exhausting, and even damaging to us. But they can be very effective at motivating us too. (Read more about this here). The following post will provide suggestions on how to add a more compassionate and constructive voice to your mix of inner critical voices.

Visualise your inner critic.

Psychologist Paul Gilbert suggests that visualising our inner critic can help us clarify and then address our self-correcting voice. Often people imagine an influential person who was (or still is) particularly critical towards them.

- Find a quiet place and grab a sheet of paper and pen.

- Focus on one particular instance when you felt guilty or ashamed.

- Visualise what your self-critic is like in this instance? What does it look like and sound like? What is its voice tone? Does it resemble someone you know?

- When you get a sense of your self-critic, imagine it sitting in a chair across from you. What does it say to you? Take a few minutes to listen to it.

Write down what your inner critic said.

We may not be fully aware of the severity of our self-criticism or the impact that it has on us. Writing it down heightens our awareness and allows us to take a closer look at its usefulness.

Conduct a functional analysis.

Ask how your critical self-talk is serving you. Our inner critic’s function is to motivate us to protect ourselves, most often by self-correcting. It ‘protects’ us by guilting (pointing out mistakes) or shaming (pointing out flaws).

1.Pick one of the self-critical statements that you hear most often. Ask, is the critical statement guilting or shaming?

- Guilt-based statements:

Is it calling you to action? I should call my mother more often would be an example of an actionable guilt-statement.

Is replacing a more difficult action? The steps required to make amends may seem too difficult (apologising or admitting responsibility), so you put them off and beat yourself up instead. I can’t even apologise. I need to be stronger.. tomorrow.

Is it punitive? Maybe you made a mistake and there is no way to make amends. But you can’t just let yourself off the hook either, so you put yourself down. How do I manage to hurt everyone I get close to?

- Shame-based statements:

Is it self-policing? Is it stopping you from acting on impulses by name-calling? Statements such as, Stop it, you are so selfish.

Is it trying to protect you? What are you doing? You can’t do that. You’ll look like an idiot.

Is it punishing? You are an idiot, don’t bother getting out of bed, you’ll only mess up.

Are you stating a fact? I am a loser. I will never amount to anything. This is a sign that your critic is not just an inner voice but a negative belief you hold about yourself. The effect of this is that every mistake you make is attributed not to your abilities or the situation, but to your self. Read more about shame, here.

2. Ask what is driving this statement. Ask three times:

What am I afraid of happening? I will mess this up.

What would it mean if that happened? I will always be a failure.

What would that mean? I am a failure.

Your critical self-talk is probably driven by this last statement. I am a failure.

3. Become aware of both its benefits and its consequences. Ask:

How well is the critical statement serving its purpose? Perhaps it served a purpose in the past but its usefulness has run out.

What are the consequences of your self-critical thoughts? They may be effective at motivating us to get things done but, consequently, we feel anxious, stressed, or insecure.

We only have to think back to a bullying coach, an aggressive teacher, or an abusive parent to recognise that bullying is not an effective way to get results, to change behaviour, or to motivate others. For example, a bullying boss may get more results in the short-term but the longer-term effects show employee burnout, sick leave, and high employee turnover.

Don’t judge your judgmental self-talk. Don’t bully your inner bully.

Right now, we are only raising our awareness of our self-critical habits. The critical thoughts are serving a function, albeit misguided. Often when we try to silence our critical self-talk, the judgments intensify. Our inner critic begins beating us up for beating ourselves up.

So, we are not going to challenge them or try to change them until we feel comfortable with the more constructive motivational and protective strategies that we have created to take their place.

Introduce to the mix a more constructive, compassionate (and effective) self-corrective voice.

Develop your self-compassion rather than your self-esteem. Our self-confidence varies from day to day. It is often based on evaluation of our achievements, validation from others, as well as comparison and competition with others. And all this makes it fragile.

Self-compassion is more robust than self-esteem because it is not merit-dependent. And it does not run the risk of being disingenuous, like positive thinking, which asks that we only focus on our positive traits.

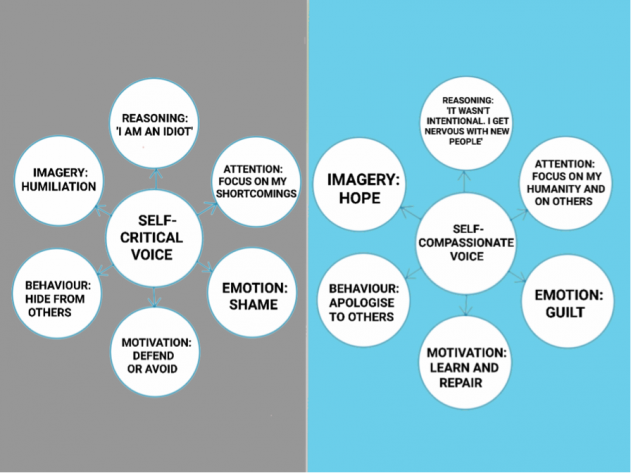

Compare how we react psychologically when we fail to meet our standards. For example: I drank too much at an event and insulted my friend’s partner.

1) Self-Critical Voice 2) Self-Compassionate Voice

As shown above in the first diagram, when we fail to meet our (or other’s) standards, our self-critical voice focuses internally on our own shortcomings, triggers shame feelings, and prompts us to become defensive or avoidant.

As shown in the second diagram, we react differently to the self-compassionate voice. Instead of triggering common coping strategies (like defensiveness and avoidance), our self-compassionate voice recognises the damage and accepts that we are fallible.

Like a nurturing parent, self-compassion views our mistakes with understanding and patience. We are more likely to take responsibility for our part and focus externally on rectifying the situation.

Internalise a supportive coach, teacher, therapist, mentor, or friend. When self-correcting, emulate the tone of someone who has been supportive and constructive – someone who accepts all parts of you, fallibility and all. If you can’t think of an example, imagine the most supportive, understanding, and.

Use your self-compassionate voice to express empathy towards the fears held by your inner critic. Accepting the fallible parts of us includes the overly-critical parts. Remember the voices are reacting to deeply-held fears. I understand why you are terrified but we might just be ok.

Example:

You can find a real-life (amazing) example of how the above exercise worked for Indigo Diya at http://www.indigodaya.com/creating-a-voice/. Here is an excerpt:

‘Together, in my journal, Andrew and I drew up a map of the different parts of me. We looked at the Judge voice that had been tormenting me, but we looked at him as just one part amongst the many parts that make up my whole. I realised that the Judge had lots of power over all the other parts, and I could see that this power was way out of balance. That’s why I was here, in this hospital.

Andrew asked me about his name, ‘The Judge’. This question helped me to see that a part of his purpose was obvious in his name: he was a critic, he was the holder of my moral values, and he held me to account against these values with a savage and unwavering focus. The Judge’s view was pretty much that I must be entirely and absolutely good and pure, or I must die. Andrew told me that almost everyone has a critic part of themselves, and sometimes they can be very strong.

As I sat there, thinking about how terrifying and brutal the Judge could be, Andrew shared his own reflection:

It sounds like the Judge has a lot of responsibility. I wonder if he might be lonely.

Wow.

Seriously, wow.

This was so very human. So kind. So unlike anything I had ever thought about the judge before. So unlike anything anyone had ever said to me before. And certainly not the kind of thing a psychiatrist might say. I was on a different planet.

Loneliness and responsibility. Not so different to how I have felt myself many times in life. When you feel responsible for a lot, and you feel alone too, it can be overwhelming. It can be hard to hold onto compassion.

Andrew’s simple but insightful little comment instantly took some sting out of my experience of the Judge. It helped me to see him as more human and fallible. It made me think, for the first time, about how the Judge might feel, instead of how I feel.

I mean, I knew that my voice and I were one and the same – but still, we were different too. The Judge had a job to do, he found it hard, and he was alone in his struggle. Maybe that was part of why he was so harsh?

A new idea began, only just, to grow in me. The idea of listening to the Judge with compassion, rather than with fear. Over time this idea would open up many new avenues in my recovery.’

Come up with constructive counters to your most destructive self-critiques.

Look back at the self-critical statements that you wrote down. For example, I am an idiot.

Ask, Would I say this statement to a close friend or to a young person who I am coaching? Look what you did. You idiot!

Then come up with compassionate alternatives to use next time that any of these pop into your head. For example, I am an idiot! can be followed by, I know that I am not an idiot – I just I drink too much when I get nervous. Next time I will have a strategy in place for drinking less.

Learn more about how to develop self-compassion.

Unfortunately, self-compassion is much harder for some of us to practice than it initially might sound, especially if we haven’t experienced supportive voices in our past. You can learn more about how to develop self-compassion by reading The Compassionate Mind or The Power of Self-Compassion: Using Compassion-Focused Therapy to End Self-Criticism and Build Self-Confidence.

References and Contributors

Indigo Diya. (2016). Creating a new voice. The blog that shouldn’t be written. http://www.indigodaya.com/creating-a-voice/

Paul Gilbert. (2010). The Compassionate Mind.

Karla McLaren. (2013). The Art of Empathy: A Complete Guide to Life’s Most Essential Skill.

Mary Welford. (2013). The Power of Self-Compassion: Using Compassion-Focused Therapy to End Self-Criticism and Build Self-Confidence.

How therapy works

Worksheets and useful information

Creative Process

Feeling Stuck

Stress

Depression

Feeling Down

Anxiety

Guilt and shame

Find out more

What I do differently

Monkey Therapy

Transformational Coaching

Online Therapy

Trauma

Your inner critic

The science behind it

Steps you can take now

Publications

More than CBT

More than IFS

Psychedelics

Neurodiversity

Thank you!

Your message has been sent. We'll contact you shortly

© 2023 The Monkey Therapist. All Rights Reserved. Site Designed By Samantha Ósk

PRIVACY POLICY